Jay Fisher - Fine Custom Knives

New to the website? Start Here

"Cassiopeia"

“Better to have, and not need, than to need, and not have.”

--Franz Kafka

Writer, 1883-1924

My tactical knife kits can be substantial. You might be surprised to know how much there is to a fully functional modern tactical, combat, and counterterrorism knife. You need a good sheath; you need it to lock or secure your knife. You need to be able to wear it, you need belt loops, and straps. You need a way to bring the wear position down on the leg, and even lower on the thigh. You may need to wear it across your chest, at your sternum. You may need flashlight holders, and even a backup flashlight. You need a sturdy bag to carry and store the components of the kit, for as long as the knife lasts.

You need also a way to sharpen the knife.

If you know about modern, high alloy hypereutectoid stainless tool steels, and you have experienced a proper long-term advanced heat treatment, you'll quickly realize that the sharpening methods of the past don't work. What does work is diamond abrasives. These are actual industrially-grown diamonds fused and bonded to a substrate metal with nickel plating that holds them there. The nickel wears away, since nickel is relatively soft compared to high alloy steels, and the protruding sharp grit is diamond, the hardest substance commonly known to man. Diamond sharpeners will sharpen any type of steel, even solid carbide; there is nothing harder.

Other "stones" including silicon carbide, aluminum oxide, water stones (Japanese or otherwise), novaculite, Arkansas stones, flints, and ceramics are all lesser performers than diamond. There is a huge industry in sharpening stones, and a need to continually sell another stone when the one you have wears out. Another prompt to buy comes in the form of gizmos, rods, tricks, jigs, and even grinders. Always, there is another device; always another purchase. I hope you recognize this sales process that dominates our industry.

Diamonds outlast all other methods and equipment. I still have diamond stones that I've been using for over 20 years, and I sharpen more knives than most people have ever actually seen.

Because I don't want to repeat myself any more on the website, here are some links to this important subject here on the website that I recommend you read. They also have additional links in their topic text that will give you even more information on the subject. After you read them and come back here, you'll know more than most people, even more than most knifemakers about sharpening methods, abrasives, stones, types, and applications.

Also related to the subject:

Diamond sharpening pads are the answer. They exist in solid steel forms, or in a mesh or network of open segments of diamond on steel inserted to hard plastic, or other forms like rods, tubes, triangles, or points.

Som of these have limited use; typically, a plain, flat diamond hone is the most useful. This is because the most likely cutting edge to dull will be the straight (non-serrated) edges of the knife. Though these may be curved, they are all sharpened with a flat pad of diamond.

Two grits are nice, but not absolutely necessary. A coarse grit can remove the most metal, a finer grit can simply refine the edge.

I started including small diamond pad folding sharpeners in my UBLX accessory many years ago, and knife users appreciated it. It's small, but can touch up an edge in the field, without a lot of weight to carry. I realized I needed a larger stone in the kit, one that could be used to fully sharpen the non-serrated edges of the knife reliably.

The diamond pads vary, depending on where I can acquire them. Most of them are dual-sided, bonded to a phenolic plate in the center. Thickness and heaviness don't matter, only that the diamond surface is flat and cuts metal.

Diamond will absolutely and positively scratch and abrade anything it touches! Particularly when build in the form of an abrasive sharpening stone, diamond is an unforgiving material, because nothing is harder. It will scratch the hardest steel, ceramic, carbide, and even agate, jasper, or jade. Diamond is unforgiving, and that is why it makes the best sharpener for the hardest, most durable knife blades.

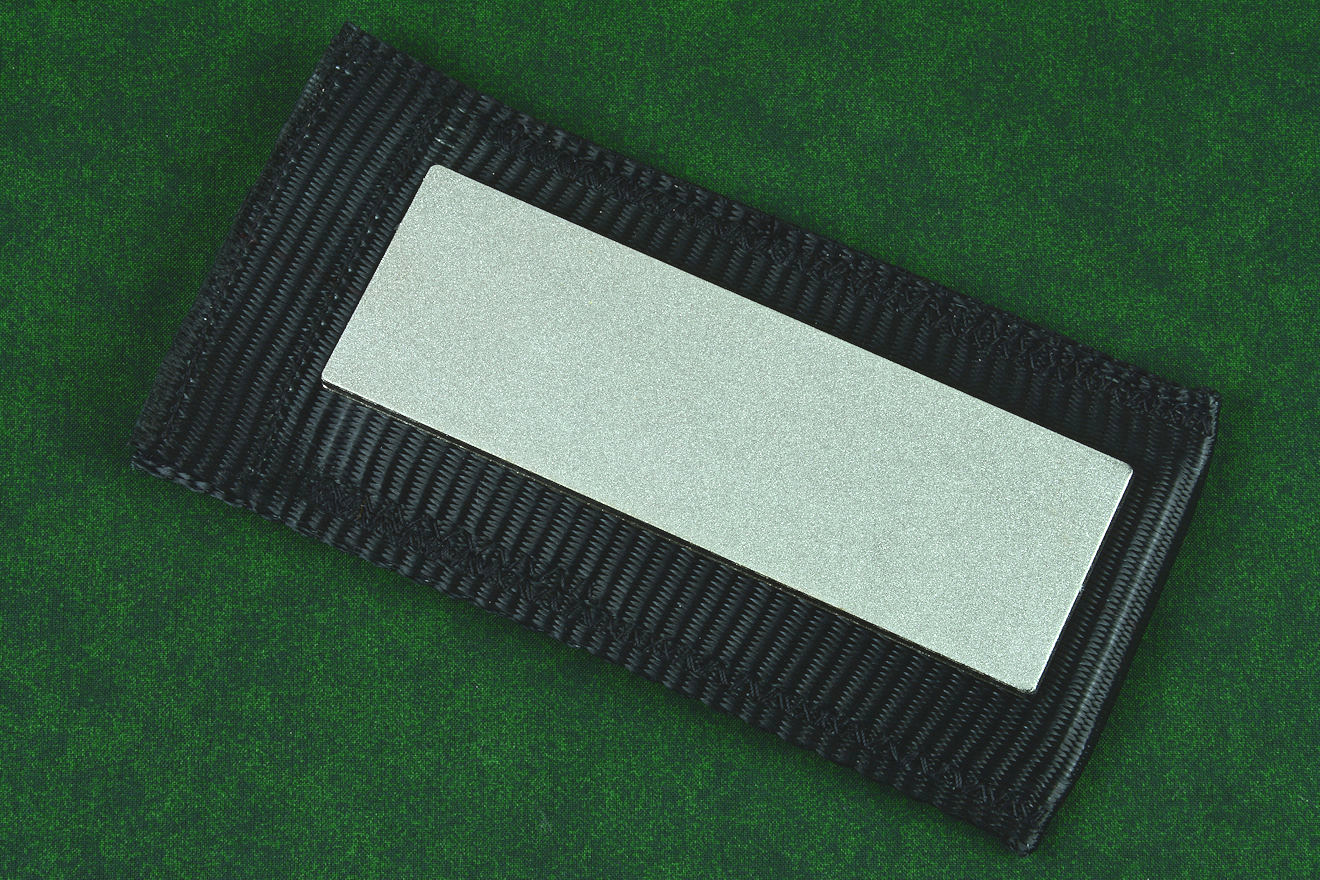

Because of this, and because the diamond hone or pad is double-sided, there simply is no safe place to lay the diamond pad. No table, no bed of any material will not be abraded by the aggressive, hard diamond grit, so I knew I had to include something that was softer, and more forgiving to lay the diamond sharpening pad on when sharpening.

This, then, became the place to store the diamond pad when not in use, since laying in the bag of the kit, the diamond abrasive will still scratch, tear, and abrade anything it touches.

I created a special envelope-style bag, a folded flap of extremely high strength, dense nylon weave. It's heavily stitched on the sides with nylon or polyester thread, and the mouth of the flat bag is secured closed with industrial strength Velcro® hook and loop fastener. The envelope-style bag is flat, and stays flat, and easily stores the diamond pad in the kit. It will take many decades of use to wear out, possibly lasting as long as the knife, since the nylon has limited give and resilience in this application.

Another nice application is to lay the knife sheath on top of the bag when changing out screws, fasteners, loops, straps, or gear. It will keep the sheath from being scratched, instead of laying it on a hard surface (like a rock or in the dirt or sand).

Simple and functional.

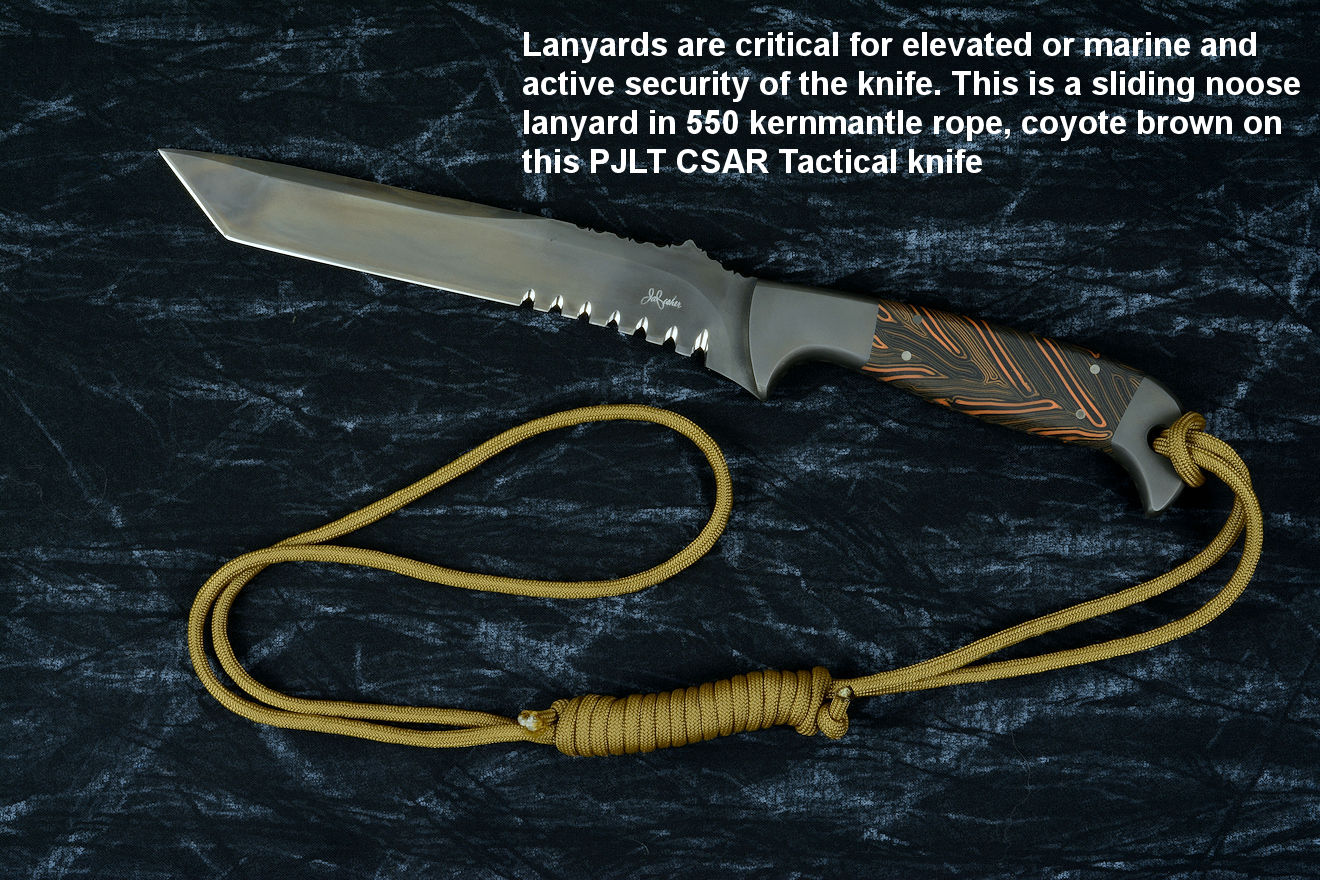

Lanyards are used to secure the knife when working in elevated positions or in or over water. If you drop your knife in these locations, it's either gone, or falling, headed for a disastrous end. To prevent the loss of a knife, a lanyard is a time-tested method for security.

Lanyards are typically short lengths of cord, and they are usually secured to the wrist. This keeps the knife close at hand if the user loses his grip. I usually include at least one lanyard in the tactical knife kit.

Lanyards are threaded through a lanyard hole in the knife handle; most of mine are at the rear bolsters. The holes are completely through both bolster sides and through the tang of the knife. The edges and corners of the lanyard holes are always rounded, dressed, and smoothed, so there are no sharp edges to cut the lanyard.

Lanyards are usually secured with a Lark's Head hitch, also called a Cow hitch. Take a look at the photos below; you've undoubtedly used this hitch before; maybe you didn't know what it was called. It's a hitch and not a knot, so the lanyard can be attached and removed with one hand (with a little practice).

The lanyards I supply with most tactical knife kits are my Sliding Noose lanyard. It's a noose, so it slides along the line, and the user can increase the diameter of one loop while decreasing the diameter of the other. It's easily tied; I've got a video up on my YouTube channel on how to tie it if you want to make your own.

I make these lanyards from nylon kernmantle rope, otherwise known as Paracord or Parachute cord. Simple and lightweight, this is strong cord. I would never use it to make a knife handle; that's just ridiculous, but it is a good lanyard rope.

I also include some lanyards made for SCUBA diving, they are waterproof, much smaller, with neoprene rubber wrist guards and pinch-slack cord adjusters.

A lanyard is an inherently dangerous device. A lanyard can snag, hang up on objects, become tangled, and bind the wearer to equipment, machinery, and even his surroundings at the most inopportune time. They can trap the user, they can catapult or sling the razor-sharp knife back at the user.

For these reasons, I recommend only using the lanyard in the minimum of circumstances, only when necessary and not as a normal accessory for the knife. Think hard about any cord that can trap, any ligature that can garrote, choke, or become entangled.

Don't use them unless you have to, and then, be very careful while doing so. Remove them as soon as you can, and store them in the kit.

| Main | Purchase | Tactical | Specific Types | Technical | More |

| Home Page | Where's My Knife, Jay? | Current Tactical Knives for Sale | The Awe of the Blade | Knife Patterns | My Photography |

| Website Overview | Current Knives for Sale | Tactical, Combat Knife Portal | Museum Pieces | Knife Pattern Alphabetic List | Photographic Services |

| My Mission | Current Tactical Knives for Sale | All Tactical, Combat Knives | Investment, Collector's Knives | Copyright and Knives | Photographic Images |

| The Finest Knives and You | Current Chef's Knives for Sale | Counterterrorism Knives | Daggers | Knife Anatomy | |

| Featured Knives: Page One | Pre-Order Knives in Progress | Professional, Military Commemoratives | Swords | Custom Knives | |

| Featured Knives: Page Two | USAF Pararescue Knives | Folding Knives | Modern Knifemaking Technology | My Writing | |

| Featured Knives: Page Three | My Knife Prices | USAF Pararescue "PJ- Light" | Chef's Knives | Factory vs. Handmade Knives | First Novel |

| Featured Knives: Older/Early | How To Order | Khukris: Combat, Survival, Art | Food Safety, Kitchen, Chef's Knives | Six Distinctions of Fine Knives | Second Novel |

| Email Jay Fisher | Purchase Finished Knives | Serrations | Hunting Knives | Knife Styles | Knife Book |

| Contact, Locate Jay Fisher | Order Custom Knives | Grip Styles, Hand Sizing | Working Knives | Jay's Internet Stats | |

| FAQs | Knife Sales Policy | Concealed Carry and Knives | Khukris | The 3000th Term | Videos |

| Current, Recent Works, Events | Bank Transfers | Military Knife Care | Skeletonized Knives | Best Knife Information and Learning About Knives | |

| Client's News and Info | Custom Knife Design Fee | The Best Combat Locking Sheath | Serrations | Cities of the Knife | Links |

| Who Is Jay Fisher? | Delivery Times | Knife Sheaths | Knife Maker's Marks | ||

| Testimonials, Letters and Emails | My Shipping Method | Knife Stands and Cases | How to Care for Custom Knives | Site Table of Contents | |

| Top 22 Reasons to Buy | Business of Knifemaking | Tactical Knife Sheath Accessories | Handles, Bolsters, Guards | Knife Making Instruction | |

| My Knifemaking History | Professional Knife Consultant | Loops, Plates, Straps | Knife Handles: Gemstone | Larger Monitors and Knife Photos | |

| What I Do And Don't Do | Belt Loop Extenders-UBLX, EXBLX | Gemstone Alphabetic List | New Materials | ||

| CD ROM Archive | Independent Lamp Accessory-LIMA | Knife Handles: Woods | Knife Shop/Studio, Page 1 | ||

| Publications, Publicity | Universal Main Lamp Holder-HULA | Knife Handles: Horn, Bone, Ivory | Knife Shop/Studio, Page 2 | ||

| My Curriculum Vitae | Sternum Harness | Knife Handles: Manmade Materials | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 1 | Blades and Steels | Sharpeners, Lanyards | Knife Embellishment | ||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 2 | Blades | Bags, Cases, Duffles, Gear | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 3 | Knife Blade Testing | Modular Sheath Systems | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 4 | 440C: A Love/Hate Affair | PSD Principle Security Detail Sheaths | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 5 | ATS-34: Chrome/Moly Tough | ||||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 6 | D2: Wear Resistance King | ||||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 7 | O1: Oil Hardened Blued Beauty | ||||

| The Curious Case of the "Sandia" |

Elasticity, Stiffness, Stress, and Strain in Knife Blades |

||||

| The Sword, the Veil, the Legend |

Heat Treating and Cryogenic Processing of Knife Blade Steels |