Jay Fisher - Fine Custom Knives

New to the website? Start Here

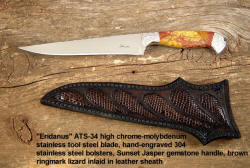

"Cassiopeia"

Right now, you are reading the best singular knifemaker's website ever made on our planet. On this website, you will see many hundreds of defined knife terms, detailed descriptions and information on heat treating and cryogenic processing, on handles and blades, on stands and sheaths, and on knife types from hunting and utility to military, counterterrorism, and collection. You can learn about food contact safety and chef's knives, you can find out what bolster or fitting material is best for each application and why. You can lean about caring for a knife, you can see the very largest knife patterns page in history, with many hundreds of actual knife patterns and photos of completed works. You'll also be able to see thousands and thousands of photos of knives, knifemaking, processes, and creations, with many hundreds of pages of appropriate, meaningful text. You might want to know why a knife blade is springy, you might want to know why a hollow grind can last longer than a flat grind. You might want to learn about some pitfalls of the tradecraft, and you might even want to have a chuckle about funny and strange email requests.

You'll find all that here, on JayFisher.com, and you won't find it anywhere else!

... to one of the most popular pages on my website, and the best knife blades page on the internet!

The knife starts with the blade, instantly recognized across time and cultures. People who visit here are looking for information, pictures, descriptions, details, and reason in a world full of hyperbole and schemes. Here you can read, in plain clear language, the details about knife blades and what I have learned from being a full time professional knife maker for several decades. Everything written here is my opinion, formed by making and selling literally thousands of knives for over thirty years to knife users, collectors, the military, law enforcement, chefs, hunters, guides, and industrial and specialty knife users. I guarantee that when you leave this page, you'll know more than most people about fine handmade and custom knife blades.

I've seen your website and it is amazing. I've used a knife for the whole of my working life. To me they are a tool, like a wrench or a screwdriver. It's difficult to get good ones designed for what you need. They mostly let you down. I work with rope and must have a sharp knife. I also need a marlin spike to splice. I must carry both a sharp knife and a marlin to do the job. Marlins are hard to come by these days but a decent knife is almost impossible now. I was looking for a quality knife then I saw your website. I want to say that in a world where I thought that nobody cared about quality or craft anymore, you've proved me wrong. Thanks for doing so.

Yours Sincerely, M. B.

Homo sapiens has been around for about 100,000 years. Surprisingly, he was not the first knife maker. Evidence shows that the recently identified hominid species, Australopithecus garhi, was a tool and knife maker, deliberately selecting and modifying specific raw materials in a sophisticated and consistent way, and with careful intent. He was making double-edged knives about 2.5 million years ago. This technology gave its inventors an astonishing advantage - the ability to shift to an energy-rich, high-fat diet which led to all kinds of evolutionary consequences.

"Fossils of Australopithecus garhi are associated with some of the oldest known stone tools, along with animal bones that were cut and broken open with stone tools. It is possible, then, that this species was among the first to make the transition to stone toolmaking and to eating meat and bone marrow from large animals."

--Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Millions of years have passed since man first noticed that a sharp flake of obsidian, flint, or agate could cut. No one knows when the birth of the cutting edge took place; it is enough to understand that the knife was man’s first tool, predating modern man (Homo sapiens sapiens). No image, figure or shape would carve his destiny so profoundly, and even today every item and component of everything we touch, eat, wear, or drive has at one time been touched by a cutting edge. We humans, without fang or claw, will always require our essential edge, and are simply naked without it. We are a creature that cuts and shapes things: our food, our clothing, our shelters, our very environment and attitudes are based on our ability to create, and that ability's first and foremost tool is the cutting edge.

The origins of the word knife are from the Middle English (450-1150 A.D.) word knif and knyf, from the Anglo Saxon word cnif. Who knows what a knife was called before that? The origin of the word blade is similar, in Middle English it was blad and blade, from the Anglo Saxon word blæd, which means a leaf.

Back to TopicsIn our modern definition, to cut means to penetrate with an edged instrument, divide or separate with an edged tool, shear, incise, or sever. So what is the common factor here? It's the cutting edge. A knife is used to cut, rather than abrade. Sandpaper and grinding wheels abrade, though in a way, they cut; they use tiny cutting edges (when new and sharp) to rip away small particles of surface material. An axe blade uses a bit of cutting force and a lot of wedging to split away the grain of wood. A lathe tool or drill bit uses a heavy, thick cutting edge to displace and separate metal from metal (at high speed) as a cold chisel would. Probably the largest difference between the knife and all other cutting edges is the ability of a knife to have a very thin cutting edge, with the potential to apply a tremendous amount of force behind the edge with only the power of the human hand. Though many modern tools used in industry are called knives, this text only refers to those held in the human hand.

Back to TopicsVery. Learn more about the handle on the Custom Knife Handles page here.

Back to TopicsThe shape of a knife blade, to a large extent determines the absolute use of the knife. Humans have made knives for millions of years. These are our most evolved and revered of tools. We've had millennia to define, refine, and perfect the knife blade, and yet there are thousands of designs. Why? (See my own 450+ designs here) Because, as simple as it would seem, a tiny variation in length, curvature, profile, thickness, and grind changes the knife completely. It's funny how just .030" of difference will make the knife blade look entirely distinctive. People notice this. I believe that man has made the knife for so long that it's possible that the pattern is somehow recognized on a genetic level. People relate to knives that way. Handles notwithstanding, I've seen clients stare and compare and tune and modify the pattern in the slightest way to reach that perfect shape that they think is just right. Where does that come from? Have they really used knives that much to be able to distinguish miniscule differences in what is right for them? There is something deeper here, something at the very core of the human psyche. That's another discussion for my book.

In a basic way, knife and blade use can be classified by shape. A long sweeping, curving blade is usually called skinning, or fleshing. A heavy, large aggressive-looking straight blade is usually called combat or tactical. I try to stay away from the term "fighting knife," as this is a negative and unrealistic designation for a modern knives.

Many knives are classified depending on the physical attributes of their profile, such as drop point, clip point, trailing point, and swage.

Other blade shapes not shown by example are curved, razor, wharncliffe, square, kris, dirk, jambiya, stiletto, spey, smatchet, hawksbill, katar, and chakmak. There are a tremendous amount of variations in knife blades, and some of the blade styles incorporate the geometry of several different defined shapes. As the knife blade evolves, some new styles will undoubtedly be named, and the clear definitions of blade styles and shapes may be blurred or even discarded. For example, it would be ridiculous to describe a knife as a modified spear point with trailing point and tanto attributes with a recurve body and hollow ground swage... but I've done that! Ultimately, a photograph or illustration is necessary.

To learn much more about knife terms, anatomy, and knife related parts, please take a look at the best Knife Anatomy Page on the internet right here on this web site!

Back to Topics

Knife blade shapes can also be classified by their use. This is a more casual affair, as most blade shapes can be used for a variety of cutting, slicing, or (in the case of combat knives) stabbing or ripping requirements. Some of the direct use classifications are: butchering, hunting, kitchen, chef's, culinary, caping, skinning, utility, combat, defense, CQC (Close Quarters Combat),assault, CQB (Close Quarters Battle), sport, camp, survival, CSAR (Combat Search and Rescue), counterterrorism, fantasy, sculptural, art, woodcraft, fillet, personal, bird, trout, ceremonial, carving, collector's, investment, museum, fine art, and simply working knives. There are many more: specialized descriptions, specialized uses, individual, dedicated knives, and knives that may cover several or many of the classifications listed.

If all knives were the same, we'd only have one design, and you would see it everywhere. Instead, you'll see thousands of knife designs in the modern world. I make over 500 different designs myself. Imagine all the varied designs created throughout history, and you'll soon realize the tremendous variety of knives. There simply is no other tool or device that has so many variations and knives are astounding forms.

The person asking this might be wondering about comparisons between a handmade custom knife and a factory knife. Though this topic comes up infrequently, it is important to educate those who may try to form a realistic comparison of these two very different origins and fabrications of the same tool, art, or piece. This discussion is prevalent enough to deserve its own dedicated page on my site: Factory Knives vs. Handmade Custom Knives. Simply put:

Factory or manufactured knives depreciate from the moment of purchase.

Fine handmade custom knives from well-known makers appreciate from the moment of purchase.

Visit the page to find out why.

Back to TopicsHi Jay, not a ‘purchase enquiry’ just a few words to say I have never seen such beautiful hand made Craftsmanship knives!

Found your Web Site on a knife search (I am in the UK) and when i saw the photos, I was to say the least, very impressed. Well done Jay, you are a true knife Craftsman.

Regards

Jim Rea FLS.

(Parks and Countryside Officer and Axe Collector)

Comparing factory knives to handmade custom knives is like comparing a hand-rolled Cuban cigar to a pack of cheap smokes.

A factory or manufactured knife can not compare to a handmade custom knife. Just because they share the same form, a blade and handle and sheath, it does not mean that they are in the same realm. Find out the difference between a knife that sells for a hundred bucks, and one that starts at 20 times that much on this special page dedicated to the topic.

In the specific and detailed subject of blades, the most important thing to remember is that factories need something to sell, something made cheaply but sold for as much as their market will bear. So for the blades, they often offer special steels that they claim are superior to the recognized AISI steels. They also are very careful not to reveal the steel alloy components or actual properties like tensile strengths, heat treating process, corrosion resistance, wear resistance and other factors and instead, claim things like, "testing has determined that our steel has superior performance, wear, and corrosion resistance than 440C, ATS-34, etc."

Don't be fooled by this hype. Any of these so-called tests are entirely subjective, and can be easily directed toward the intended result, which (shock) is always in favor of their special steel. Without revealing the exact components of the steel, there is no scientific way to test it. This is because testing, real scientific metallurgy must have as its basis the knowledge of the steel alloy components and method of manufacture as well as all the properties, mechanical and exposure, that the steel has or will be exposed to.

Let's make a simple, realistic comparison. A skyscraper is under construction. The head engineer of the ironworks company has read on the Mystical Bolt Company website that bolts are available, to assemble the structural steel columns, that they are a special and secret alloy and they perform better than known, recognized, and accepted industry standards. No technical specifications exist on the bolt maker's site: no alloy content, no process of manufacture, no tensile strength, impact strength, yield, elongation, area reduction at specific hardnesses and tempers depending on specific and varied heat treating and manufacturing processes is offered. On the bolt maker's site are just vague generalities about performance. Not one engineer on earth would sign off on the purchase of this fastener for the integrity of its properties and application on the project without knowing even what the material is.

Yet in the world of knife manufacture and sales, it's almost expected that the knife factory or boutique shop (small knife manufacturer) will supply some special, proprietary, or unique and mysterious steel that outperforms all other known types. Really? It seems each factory follows the same advertising formula, claiming a special designation, comparing in generalities the qualities to known types, claiming superiority and thus value, sometimes adding performance anecdotes like chopping pine two-by-fours, shoving the blade in a car door, or bending, leaving submersed in water, or other ways of brutalizing a piece of overly thick steel. Then, to top it off, organizations and interests claim that certain knives must be certified (by them) for the honor of being tested in this anecdotal, subjective, and extremely unscientific way. Usually, this requires the donation of a knife or knives for this honor!

This is all advertising hyperbole, so that you will think that the inexpensive factory knife is somehow superior to other inexpensive factory knives. All the while, the knife lacks balance, has an unfinished blade, is poorly fitted, has cheap or non-durable handle materials, poorly made or non-existent fittings, no contouring or radiused forms, horrible fit, weak mechanical construction, lack of bedding, poor design, simply awful sheaths or accessories (or none at all), and no service, except for one or two companies who will sharpen your knife for a fistful of dollar bills. These knives will never be worth more than they are when they are purchased, never have any long-term value, are not custom, are not well made, and most individual knife makers create a product that is many times and many ways superior to factory or manufactured knives. But since the factory's business is built on volume, not quality, this doesn't matter.

Thankfully, the internet is changing all that. This very medium has been the source of real, valid information in not only the field of knives, but it all fields of interest and knowledge known to mankind. No matter where you live, you are very lucky that you are in a country that allows the technology and access that allows you to read this very sentence, and that you are living in an exciting time of the growth of knowledge and ultimately truth that the Internet can bring. You've just got to wade through the hype to get to it!

In my book, I'll go through just how significant and powerful this opportunity called the internet is, and how it's changing the way people do business, access products, learn, grow, and excel, deepen, and enrich their lives and the lives of their families with this tool of knowledge. I'll also detail how the vague, indiscriminate advertising hype that was started in print media that was limited to "pay by the letter" generalities has to face the reality of fact-based transparency. The practices of using power words and catch phrases is falling to the detailed and specific facts of product properties. But the factories don't get it yet, and maybe, because their products are cheap and made en masse, they never will.

Have you heard of this new thing called the internet? It's giving people new expectations. It's allowing them to become their own expert. Knowledge lies anxious at their fingertips. Gloss over the truth in your advertising and you'll quickly be dismissed as a poser.

--Roy H. Williams

My point about steel types, blades, and hand knives is simple. There are known and listed steel types with known and listed mechanical and exposure properties. They are known and listed by real entities like the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI), the Society for Automotive Engineers (SAE), and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). They are listed because they are established materials in industry, the military, and even the medical equipment fields. If there were a really special steel, something so great that it lived up to the advertising hype posted on these factory knife sites, wouldn't you see all other steels tossed aside and become obsolete while the new steel took over the military industrial commerce? Of course you would. Established and well known steel types exist for a reason, and each reason varies in our world. There is no steel that dominates in all realms. A super hard steel may be brittle, a wear-resistant steel may easily corrode. A lightweight material may be soft, a high wear resistance material may not be able to be finished or sharpened by hand. Every material has its pros and cons and I list those on this very page. You won't find factories listing any cons on any of their products, yet they do not supply a knife that is good enough to choke out the competition. Please think about that.

Please help to stop wives' tales, knife myths, and misconceptions in our trade through education.

Back to TopicsJust found your website – New item on my bucket list – to one day have you create a knife for me!

Beautiful knives, website and very informative; I just spent the last couple of hours (maybe it was more

like 4 hours) reading some of the most straight forward and insightful knowledge on knives. My head is spinning !

Wow and wow – thanks for all of the hard work on creating your website and one day . . . a knife of yours will be mine!

--Danny Schmider

Dear Jay

I can truly say I have never seen such beautiful work before. I came on your page looking for knife cases and

yes, I realize you don't make them. But I wanted to take a moment to say that you have an incredible sense of

artistry. As a custom furniture builder, I have a bit of an appreciation for what you deal with - but you are

way beyond anything I ever accomplished. I now am a manufacturer of mass produced outrigger pads and don't miss

the hard times of building furniture. Anyway, great job, excellent work.

Bravo.

Bob Lifton

Of course not. They run the full range of quality from low to high. Some flat grind, some hollow grind, some stock remove, some forge, some assemble kits. It's best to educate yourself about knifemaking in general, but here are some points to look for:

There are several ways to verify the knifemaker's reputation. Who does he make for? He should have that right out front, for all to see. He should have no problem telling you who he makes for, what they use the knives for, what his current knives are valued at. Does he have a past history of shows, membership in professional knife organizations, or publications of his work? Does he have a professional website or archive of his past works? Where are his knives now? Are any in museums, collections, or displays? Can he give you any names of people who have used his knives and like them? Can you see pictures of his knives?

These sound like simple, obvious questions, but you would be surprised at how many clients are distracted, played, and conned by knifemakers. Here's an example: I attended a show once and my table was next to a female knifemaker, who immediately claimed to a prospective client that her family had thirty years of knife making experience. She was in her early twenties and laid claim to her family's experience as her own! Those years of experience were not apparent on the knives laying on her table, as they were big and blocky and badly finished and out of balance and ugly. Then, she gave the prospect some BS about the mystery of heat treating, how it was a special family secret handed down through generations. I bit my lip, knowing that heat treating is specifically described and prescribed by the manufacturer of the steel, that it is right up front in all engineering specifications for all knife steels, that it should be clear and simple to the client that the maker is treating the steel just as specifically as the manufacturer requests for the intended use. But the worst part is that she giggled and feigned interest in the client, smiling and flirting, and that kept him looking at her more than the knife.

The truth here is that some men are easily swayed by the attention of a young lady. He'll walk away with an overpriced hunk of junk, and the memory of a brief encounter with a con. Is it worth it? I wonder how the line of BS would have gone down if his wife was standing beside him—

The moral here is look, look, look.... at the knife (and the sheath). The knife itself should be your focus of attention. Yes, you want to know the reputation of the maker, you want to know he's had years of experience and trustworthy clients. Still, take some time and examine the knives or the photographs very closely in front of you, they should speak for themselves. Listen to what the knifemaker says; does it make sense? Can the knifemaker answer your questions with intelligence and dignity?

That brings me to another professional aspect of the knifemaker: his appearance and attitude. Do you like buying from a loud-mouthed polyester prince used car salesman? Are you comfortable with a cowboy all duded up with his best brushed felt range hat and high boots more suited to stomping through cow dung than presenting fine work? How about that guy wearing a tee-shirt with rude graphics and holes in it and a goofy, grimy baseball cap? Are these professionals that you would hand your hard earned trust over to?

The reason I include this topic is because every knife or craft show has this type of knife maker. So, does the knifemaker look, act, write, and present himself as a professional including here on the internet? Don't get me wrong; if someone comes to my studio and shop, and they catch me with my full-face respirator and metal swarf-covered coveralls and work boots covered in wood and rock dust, I'm still a professional. But I wouldn't be caught dead at a knife show in that get-up. It's just not professional.

There is no miracle about making knives. Making knives is the oldest profession around. Yes, before even that one. Men have made knives for literally millions of years, for without a blade, early man would have starved. It is an honorable profession, if presented honorably. There is no great mystery, just practiced skill and determination. There are no magic secrets to steel ingredients, to heat treating, to knife or blade shape, geometry, or materials. There is no enigma in the blade, no mystical materials; we don't quench in the blood of our enemies. There is no romance to the cutting edge, only artistic interpretation. No sword or crystal has magical powers, steel can't cleave stone, and a suitable dagger will not allow you to fly. Fine knives come from trained and practiced hands, not from a hidden tomb in a mountain. They are tools and sometimes works of art made by people like me who love to make them.

I take this business seriously; it is my full time professional job. I respect my clients and share their interest and love for the finest knives.

Back to TopicsYes, Virginia, there are specifically classified tool steels, and they are specifically used to make tools for the working and forming of woods, plastics, and other metals. This is the definition of tool steel (from the Machinist's Guide). They have to withstand high loads, abrasive contact, elevated temperatures, shock, stress, and adverse conditions without suffering major damage, edge dulling, or metallurgical changes.

Not all tools are made of tool steels! Tools used to cut wood, make hand saws for woods, ordinary hand tools, hammers, chisels, and files are often made from standard steels in the AISI/SAE/ASTM categories. The tool steel category is a separate group, and must absolutely be heat treated, hardened, and tempered. There are a large number of tool steels, with specific and controlled alloy compositions. Industry has created a specific classification systems for these tool steels in seven categories. They are:

These categories are only the beginning of specific identification of tool steels and uses. Each category has sub-categories, and many steels cross over to a variety of uses. For instance, O-1 and D2, two of my favorite tool steels, are in the category of Cold Work Tool Steels. They are hardened by quenching in either oil or air, so the hardening method is not always the designator of the tool steel category. You might hear someone group metals as "oil-hardening" or "air hardening." These are NOT individual recognized categories, the specific seven categories are listed above. Hey, I didn't make this system up, it's the industry standard!

Stainless steels have a different classification system. It's unusual, because in AISI/SAE/ASTM, in order to classify as a stainless steel, they must contain at least 11.5% chromium. But the practice by some companies in the steel industry has been to claim steels with as little as 4% chromium as stainless steels! For aqueous corrosion resistance, 12% is required. Some steels, like D2, for instance, contain 12% chromium, but are actually in the category of Cold Work Tool Steels, not specifically limited to the stainless steel category, even though D2 is a stainless steel. Stainless steels are one of three types:

In industrial standards (which we as machinists refer to) the term stainless steel refers to high-alloy steels which have superior corrosion resistance to conventional and carbon steels because they contain relatively large amounts of chromium (more than11.5%). In a broad sense, standard stainless steels fall into one of the three categories: (austenitic, ferritic, and martensitic).

Austenitic grades of stainless steels are non-magnetic in the annealed condition, but may become slightly magnetic after cold working. They can only be hardened by cold working, and do not harden in heat treat. A good example of austenitic stainless steel is 304 or 18-8, used for many stainless fasteners. I prefer 304 SS for many of my bolsters and fittings, as it is highly corrosion-resistant, extremely tough, and requires no care. Please remember that the material I use in my bolsters is the same material as most stainless steel bolts, screws, and fasteners, built for strength, durability, and longevity.

Ferritic grades are always magnetic and contain chromium, but no nickel. They can be somewhat hardened by cold working, but not by heat treatment. They have moderate mechanical properties, high decorative appeal, and a narrower range of corrosion resistance. Some of the ferritic grades contain alloys that help prevent hardening. A good example is 405 stainless, which is often used because it can be easily welded and used in the as-welded condition, and is soft and ductile.

Martensitic grades of stainless steel are magnetic and can be hardened by heat treating, quenching, and tempering, forming martensite. They contain chromium and with several exceptions, no nickel. Many of the martensitic grades contain increased carbon content (above 0.8%, which makes them hypereutectoid) in the tool steel range, and are hardenable to the highest levels of all the stainless steels. Though they are not resistive to extremely corrosive atmospheres like concentrated chemicals, acids, and caustics, they have excellent service in most atmospheres and exposures. 440C, for instance, is used to make corrosion-resistant ball bearings, high-wear valve parts, molds and dies, and of course, fine knife blades.

You'll see me referring to these grades in my description of knife steels and fittings I use in my own work.

Now if this is not confusing enough, here are the specific designations of steels (which are separate from the classification or the category). This is the standard, held by AISI (the American Iron and Steel Institute) and SAE (the Society of Automotive Engineers), and is the coordinated industry standard of steel designation:

Okay, I hope that clears it up! Want to know more? Pick up a copy of the hundred dollar book, the Machinery's Handbook© and the Study Guide at a bookstore or on line. There's more info in there on steel and other materials than you'll probably ever need!

Back to Topics

"There never was a good knife made of bad steel."

--Benjamin Franklin

Many of us older guys grew up with our fathers boasting about their carbon steel hunting and butcher knives and how they were so much better than the stainless steel blades. Unfortunately, this is one of the most prevalent and enduring misconceptions and wives' tales that persists in the modern world of knives.

There are two phases to this problem. First, in the early part of the 20th century, when stainless steels were at their infancy, the addition of chromium prevented full martensitic transformation, leaving lots of unstable retained austenite, which showed up a high wear and instability. It was only later that it was discovered that a sub-zero quenching of knife blade steels would give a fuller, more complete transformation into martensite, but the bad reputation of stainless steels had already been established. Even though the problem was gone, the myth of bad stainless steel persisted.

Claiming that a steel is a high performer does not make it so.

Look, instead, how the steel is used in the consumer, industrial, and machine tool fields for the truth.

Second, low carbon Japanese stainless steel (420, AEB-L, 13C26, and equivalent low carbon, medium chromium stainless) was introduced into the world of cheap kitchen knives in the 1960s and 1970s. If you were alive then, you remember the ridiculous commercials showing the imported junk knives pounded through cinder blocks and then shaving off tomato slices. The common man ate up this drivel, and lots of money was made in the low-end kitchen knife market based on this hype. The truth is, this type of knife was made of cheap, springy, and thin low-carbon series stainless steels, which were tough, but not hard or wear-resistant. So when the edges did wear down, it was not reasonable to sharpen them, and they were left dull, but were still thin enough to be forced through foodstuffs and other cutting chores. The eternally dull knives ceased to perform, were not easily sharpened like the carbon steel knives, and the failure to understand sharpening of this different steel meant that the stainless knives were left dull. It followed then that people assumed that they couldn't be sharpened, so the steel was blamed. Most people then made a casual assumption that the stainless steel blades were of low value (the price was a good hint), and saved their most important cutting chores to high carbon, non-stainless steel butcher and hunting knives, because they were relatively easy to sharpen and they held a very keen edge a longer time than the imports.

The stainless steel is no good myth continued, and continues today, despite the fact that the majority of knives from cheap imports to fine collectors knives are made of stainless steel. Some people still long for the good old carbon steel knives from the past.

One of the world's most respected knife historians and experts writes:

"I have owned about 10,000 antique kitchen and butcher knives, and examined perhaps 20 times that number. I have found that good quality modern stainless steel knives, when properly sharpened, are superior in use to all older knives, even the very best. Stainless steel knives can be made at least as sharp as carbon steel ones, they stay sharp many times longer, and of course, they do not stain... the president of a major knife company put it very well when he said to me that preferring carbon steel knives over stainless steel ones is like preferring vacuum tube radios over transistor ones."

--Bernard Levine, Levine's Guide to Knives, 1985

Please look at the date of the above excerpt. Since the mid-eighties, there have been many new and improved stainless tool steels become available, so the old wife's tale is even more flawed. One of the problems does continue, however, and that is the infomercial that still claims cheap Asian imported knives are worth your hard-earned money. This myth of carbon steels extends into the handmade knife field, and bears examination.

Carbon Steels: Carbon steels, properly identified as Plain Carbon Steels by the AISI, SAE, ASME, NSI and ANSI are typically are identified by number. If the four digit number starts with 10, it is a plain carbon steel. Typically, in the knife trade and industry, 1025, 1075, 1080, and 1095 are often used. 1095 is about the best one can get for a plain carbon steel, as it has up to 1% carbon. It has manganese in it to increase forgeability, reduce brittleness, and improve hardenability, though the manganese does not itself improve hardness. No other notable alloy elements are included. These steels are usually chosen because they are inexpensive, usually about one fourth of the cost of stainless tool steels, and one tenth the cost of crucible particle metallurgy tool steels. These carbon steels are easy to work, are ductile and soft when annealed, and are gentle on tools and abrasives. Simply put, it is easy, cheap, and fast to make a knife from any of these steels. They have absolutely no corrosion resistance, and will quickly and easily rust and pit when left in the open air. They are easy to sharpen because they are not wear-resistant, and they frequently dull. In my experience, they are a bad steel for any knife. The only exception in my studio is when 1095 is married with nickel for nickel damascus in decorative blades. More about that below.

Another commonly seen type of knife steel used by makers and the knife industry is 5160. Though technically classified as a chromium steel, 5160 has very little chromium (.08% - 1.0%) and is not corrosion-resistant in any way. The chromium is added to slightly improve the hardenability, but not enough is added to increase corrosion resistance or aid in the creation of an abundant amount of chromium carbides which can increase wear resistance. The chromium is limited because if added in significant quantities, the forging and critical temperatures of the steel would be raised enough to prevent hand-forging. Though this steel has better performance characteristics than the 10XX series, it is still not suitable for many knives, simply because it easily and readily rusts in the open air, and does not have high wear resistance. It is chosen mainly because it is a cheap steel, one fourth the cost of stainless high alloy tool steels, one tenth the cost of crucible particle metallurgy tool steels, and is easier to machine, cheaper to finish, and more forgiving to make a knife with.

Simply put, plain carbon steels are cheap steels, and have no place at the top of the line for extremely fine knives.

What are the advantages of the better high alloy tool steels? There are many, and they are different. These modern, engineered, fine isotropic tool steels are created for the distinct application of creating tools and wear-resistant parts and cutting edges. They are the finest tool steels humanity has ever produced. In the application of blades for fine knives, there are some distinctive advantages, mainly high corrosion resistance, high wear resistance, high toughness, high tensile strength, and high finish value.

You might then ask the question of why these higher value, extremely fine steels are less often seen on knives. It's really very simple. They are expensive, they are very difficult to machine, cut, and make a knife with, they are unforgiving of error or mistake by the maker, they are hard to work, resistant to abrasives, and a supreme challenge to properly finish. They require special treatment in vacuum-nitrogen furnaces or controlled atmosphere environments when heat treating, they require extremely high critical temperature transformation points, and extremely low temperature quenching points, they are demanding and specific in their treatment to yield a superior cutting blade and knife. This is why they cost more to the knife owner, and why most makers and manufacturers do not offer these steels on their knives. This is the price for being the very best.

I dare you. Here is what other knifemakers, companies, and manufacturers of carbon steel knives don't want you to ever know!

I take no responsibility for any injury that may occur during this test! If you don't have good motor control, and can't follow simple, logical instructions, do not perform this test! If you are super sensitive to taste, do not perform this test! In fact, if you have any trepidation at all about this test, simply read this section and learn.

If you really need a clear demonstration of the limitation of carbon steel (non-stainless) to prove it to yourself, I've developed a simple test. This was not done with technical help from metallurgists, research scientists, or promotional and advertising professionals. This was developed in a simple moment, with logic, common sense, and clear intent.

After you perform this test, you will never, ever again consider carbon steel of any kind for food service, for exposure use, and possibly for any knife, unless it's surface treated or hot-blued. Even then, you won't want it in the kitchen at all, ever again in your lifetime! You won't want your meal prepared by anyone who uses a carbon steel knife, you will seriously avoid those sushi bars where the chefs slice up raw fish and vegetables with a dark, funny shaped thin carbon steel Japanese-named knife with a straight handle and a stick tang. You might even start asking your butcher, favorite restaurant owner, and accomplished chef what they use for a knife, only to correct them by suggesting this very test! You think I'm exaggerating?

Read on and pay strict attention; I'm about to change your perception of carbon steels forever!

That's a pretty bold claim, and you might think I'm just trying to sell you an idea, but here's the thing: you will make this transformational decision by yourself, once and forever, and you'll never go back again... ever. Your own experience will be so profound that you will show others. Others will be transformed, instantly. My only request is that you properly credit me for this test by using my name, Jay Fisher, and maybe even include my website: www.jayfisher.com in your repeating of this test.

You don't need any special equipment for this test. You will need a few basic items that you, no doubt, have, since you are reading this text:

Take both knives to the sink, and clean them well. Use soap and water (anti-bacterial or dish soap is common and accessible, and what you would be washing the knife with anyway). Be careful not to cut yourself, scrub the blades clean of any oil, fats, or greases. This is just like cleaning your silverware or cutlery in your own kitchen. Of course, be careful of the cutting edge; you don't want to slice your finger. Get the blades as clean as possible, like your silverware. Dry them.

The test:

Spoiler alert! Don't read this before performing the test if you want to experience the full effect!

Here's what will happen: Your tongue will start to salivate as the carbon steel reacts with the moisture. You will feel an astringent pull—kind of a dry chemical reaction—before the ever-increasing glow of full iron overwhelms your entire tongue surface in contact with the steel. The bitter iron taste will be strong: stronger than blood when you bite your lip, stronger than you will ever expect. The iron will permeate your tongue, and dry and sour the entire surface of your tongue for at least 30 minutes after you've pulled away in utter disgust. You will slobber, you will pucker, you will hate the taste that is now stuck on your tongue. It's as bad as being burned by hot coffee in a hasty sip, worse than any bad cheese or salty lemon you have ever experienced. You will absolutely hate it, it won't go away until your mouth is fully rinsed and cleaned! The taste effect may literally last for hours! I could still taste the corrosion after 8 full hours and several meals!

Your conception of carbon steel blades will be changed forever and instantly, and you will thank Jay Fisher.

Now, test the stainless knife. Heck, you don't even need a knife, because this will be the same as putting your mouth on your stainless silverware. Nothing will happen. You'll be surprised that there is no taste, no flavor, no iron, no reaction. This is why we have stainless steel cutlery, after all.

What has happened and what it means: The moisture in your tongue along with oxygen in the atmosphere has reacted dramatically with the surface of the steel. The steel has immediately broken down in a chemical reaction, producing iron oxide which is essentially rust. The oxygen aided by moisture combines with the metal at an atomic level, forming a new compound called an oxide and weakening the bonds of the metal itself. Rust consists of hydrated iron(III) oxides Fe2O3·NH2O and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeOOH, FeOH3) Surface rust is flaky and friable, and it provides no protection to the underlying steel. You are eating rust, and rust is now bonded to the surface of your tongue. You will probably experience temporary dysgeusia, a distortion of the sense of taste. Dysgeusia (dis-goo-see-uh) is not a pleasant experience, but it will go away.

If you don't clean your tongue-mark off the carbon steel blade, and revisit it in a couple hours, you'll see the contact area in clear discoloration. Sometimes, this only takes minutes. Since rust is permeable to air and water, corrosion will continue. Left alone, overnight, the steel will start to darken more, in another day, you'll see microscopic flakes, followed by pitting.

If you really like the taste of your carbon steel blade, let it pit and flake and start to dissolve into light flecks and then use a wire brush to sprinkle them on your cereal, or perhaps your cappuccino, hot dog, or steak. Nice colors can be presented over potatoes, a kick can be added to your chilled watercress soup or your mango-lime cheesecake.

If you think I'm being overly dramatic, and realize that chefs and cooks have been cooking with carbon steel blades for centuries—so why would Jay complain—think of this: since the dawn of stainless steels, all table cutlery has been made of stainless for a reason. Sure, there are some gold and silver spoons and forks, and they don't have a reaction with your tongue, either. But there are no carbon steel cutlery sets for a reason. In man's history, stainless wasn't available until the early 20th century, and then, it wasn't wear-resistant, so we were still stuck with carbon steel knives. That all changed in the latter part of the 20th century, and now we have incredible stainless steels, far superior to carbon steels, but no one has told the chefs, or they simply can't afford them.

The reason for all this is that corrosion instantly occurs upon exposure in carbon steels, and it's detrimental to the dish, the food, and the palate. A knife slicing through a piece of fish may well move fast enough to not flavor the fish, or you may have just gotten used to the hint of steel, so slight as to not be perceived. Perhaps it's overwhelmed by the taste of the fish, but it is still there.

Worse, the carbon steel is corroding at the cutting edge. It's dulling and dissolving quickly and at every slice, so the chef or cook is constantly scraping his cutting edge on a steel or porcelain rod, which flakes off the corroded surface (swarf) and deposits it wherever it can. This can be on the surface of the knife blade, on the next piece of food cut, or on a nasty rag the chef uses to wipe off the metal swarf hanging from his waist or draped over his shoulder.

One more important thing: the test you performed was with the moisture on your tongue. The pH of your saliva is about 5 to 7, slightly acidic. What do you think happens when carbon steel blades are use to cut tomatoes (3-4 pH) or lemons with a pH of 2? How fast of a reaction and how deep the corrosion then?

My point here is... WHY? Why do this when fine, well-made high alloy stainless steel blades are available, and they don't react, rust, pit, stink, or sour your food? Why are makers and foreign (Japanese) knife companies pushing carbon steels?

They are doing it because it's cheap, fast, and easy to make a knife from carbon steel, and you can whip up a cutting edge with a chef's steel (rod) quickly since they are so soft to begin with. A good, high alloy stainless steel blade needs to be sharpened once a year or so, a carbon steel blade once a day (or session).

Don't fall into the carbon steel trap! Do the test, make others do the test, impress your friends and family, and be done with carbon steel knives, particularly in the kitchen, the most knife-important place on the planet!

I dare you.

Back to TopicsDon't group all stainless steels together; they can be dramatically different!

Are there still bad stainless steels use in knives? Of course there are and they are typically and nowadays found on cheap stainless knives imported usually from China, India, Taiwan, or Pakistan. Unfortunately, there are also large, older American companies that still use this horrid steel. These are 420 series stainless steels, which are worth some serious discussion.

420 stainless steel can be very corrosion-resistant, and can be very tough (resistant to breakage, flexible without breaking). But please anchor this point into all of your arguments and consideration about this steel: It can only be hardened in its maximum hardness to 51-52 HRC or (52 Rockwell on the C scale). This is substantially and markedly softer than a 440C stainless steel blade, which is typically hardened and tempered to 58HRC, and often higher. 51HRC is softer than knife blades, gouges, and much softer than drills used to drill brass or wood. 51HRC is softer than augers, chisels, axes, and even sewing needles. 51HRC is softer than a leaf spring, screwdrivers, softer than even the cheapest hand-saw for wood that you can sharpen with a file. Yep, that 420 stainless steel blade that is now on most Ka-Bar knives is soft at its very highest potential of hardness, particularly when compared to fine high alloy stainless steel knives. Most of the Ka-bar knives are made of 420 stainless steel, and you'll see a sneaky advertising ploy from the manufacturer of these steels claiming the hardness is 52-58 Rockwell. This is a ridiculous, huge range of hardness, which tells me that they are either careless about their heat treating, or they want you to ignore the 52 and hope that you'll think their knives are harder (they aren't and can't be if they are 420 stainless steel). Why can't 420 be made has hard (and wear-resistant) as say, 440C? Why that's simple, by looking at just one alloy component: carbon. 440C has over ten times the carbon of 420. TEN TIMES!

Make no mistake; the big name knife manufacturers here and overseas are mostly using 420 stainless steels. I use the phrase "420 series" because they may have variations, versions that have slightly higher carbon content to push the hardness up somewhat, but this is still a bad, cheap steel for any blade. Remember that 440C has ten times the carbon. They make claims on their web sites and promotional material how great 420 is, but now you know the truth.

After reading this, now you know why those cheap 420 series stainless steel blades gave all other stainless steels a bad reputation, and will continue to do so. Why do these companies and manufacturers use 420? Because it is super-cheap, easier to stamp out, grind, machine, work, and manufacture a knife with, and that represents a substantial savings to them, not to the person who wants the best knife steels for his investment. Don't group all stainless steels together; they can be drastically different!

Please help to stop wives' tales, knife myths, and misconceptions in our trade through education.

Back to TopicsHello Mr. Fisher,

Thank you for your willingness to share your knowledge through your website. I have learned so much and have had my view on knives permanently

altered by the knowledge I gained from reading your website.

I will begin the same way as many of letters you receive by saying “Thank You!” Your website and the information you provide are extremely appreciated. Factory made knives are ruined for me now that you have provided a framework for me to logically think through what they are offering. I will admit that I was taken in by what you refer to as the “mysticism” of the knife industry until I read your site. I am a mechanical engineer for an aerospace company and as I read your site, all of your arguments were logical and matched to everything I had been taught in school. My whole perspective on what a good knife is has changed.

--T. S.

I was shocked when I read on a knife maker's website that "Chromium prevents the steel from rusting but significantly degrades edge holding capabilities of the steel. All steels are composed of grains of the various alloying elements, the relatively large size of chromium results in a blade that will quickly dull and be very difficult to re-sharpen."

I was saddened when I read this, because it's completely wrong. It was easy to see why this guy wrote this; he's making damascus chef's knives, knives with blades out of 52100 low alloy carbon steel, and he's trying to paint a better picture of his low alloy carbon steel. If you buy this guy's statements you are, sadly, misinformed.

Let's get this very straight and clear. Chromium is an alloy that HELPS hardness, hardenability, and wear resistance, forming chromium carbides which are extremely hard and wear-resistant, quite the opposite of what this guy claims. It's unfortunate that he hasn't educated himself by reading a book on tool steels and metallurgy before he made such horrid misrepresentations on his web site.

From the Machinist's guide and AISI standards: "Chromium improves hardenability, and together with high carbon provides both wear resistance and toughness, a combination valuable in tool applications."

What? How could this be unclear? Why would this fellow make such a ridiculous claim?

It's simple. He's making chef's knives from 52100 carbon steel, and he's trying to justify why you should purchase a lesser steel blade from him. 52100 is the worst type of steel for chef's knives; it will rust at the first opportunity, it is not Food Contact Safe, and is not even a tool steel. 52100 is listed (in machinist's and AISI standards) as "a straight chromium electric furnace steel, and is of medium hardenability." A couple things stand out here:

From this, the misconceptions are pretty clear; he is either uneducated or he's lying. He drones on about the grain size of the various steels (which has nothing to do with wear resistance), and the "bonding" between the grains (which is just gibberish and nonsense), trying to convince the reader that somehow the cheaper, lesser low alloy steel is somehow better than chromium tool steels.

Look, it's okay to make a knife from 52100 low alloy carbon steel; many makers do. It's a decent steel, and can be hammered into a wear-resistant knife blade with limited use. But to claim it's somehow superior to high chromium and high alloy tool steels is just a lie; it is far inferior to high alloy tool steels, that's why they are the premium materials in the finest knives, tools, instruments, and components in wear-resistant industrial applications.

In any case, this is not the type of steel for any chef's knife, as it will corrode away at every opportunity, at the cutting edge, on the surface, and in any part of the blade where moisture from any source contacts it. It will stain, rust, pit and stink, as it corrodes into your food. This application for the kitchen is just wrong, and that is why it's not a Food Contact Safe material. Why would you punish a client and knife owner with this? Read much more about this atrocious practice of rusty, carbon steel knife blades inappropriately made for the kitchen on my Chef's Knives page at this bookmark.

Please help to stop wives' tales, knife myths, and misconceptions in our trade through education.

Back to TopicsWhether is CPMS30V, 440CPV, BG42, CPM(T)440V, SM 100, AUS10 CGRF8X0LG, or BR-549: you're convinced. One of these "new" steels is the answer to your knife dreams. The steel will hold a razor's edge forever, can be hammered through a steel anvil, bend 45° without breaking, never rust, weigh only a feather, pry diamonds out of raw stone, then shave your facial hair, cut the umbilical cord on your new baby, send waves of terror through aggressors at the mere sight of it, send waves of awe through fellow collectors at the mere thought of it, and preserve freedom for all mankind. Oh, and it can be sharpened by passing it through a summer breeze. Really?

Hopefully, you've read about the factory practice of special steel designations in the topic above, and more information on these practices are detailed on my Handmade Custom Knives vs. Factory Knives page.

I get these questions all the time. Is this latest craze or a gimmick, or is there a real new miracle tool steel? If there were a miracle steel, don't you think that it would sweep the country, be used on the latest high quality military grade and medical machines? Wouldn't it be used to cut other metals on machine tools like lathes, mills, boring machines, planers, drills and other machines? Why, of course it would. So what is all the hoopla about?

Pop steels, that's what. In the 1980s it was 154CM, in the early 1990s it was ceramics, in the late 1990s it was BG42, and lately it's been CPMS3V. Look, they are all good steels (except ceramics, and nickel-titanium alloys which are not steels at all) and they all can make and still do make a fine knife. I've used most of them, but they all have limitations as do all blade materials. So why are these pop steel trends so prevalent?

Factories, knife makers, dealers, importers, and salesmen always need something new. That is because they must continually sell the hyperbole, to generate interest in their product. Usually, this is because of poor overall product design. In knives, the fit and finish and balance and accessories are all labor-intensive high skill areas of production, and the fine hands-on workmanship required to make a fine finish, fit, balance, and accessories often does not happen. Factories and makers of low quality knives then rely upon gimmicks, tricks, hype, and envy to sell their product. So, every couple years, a new steel hits the market and all the guys are talking about it. It's on the forums, in the magazines, and in discussions at shows. It's the future of knife making, lots of sales are made based on it, and then it just fades away as another gimmick steel name starts dripping off the drooling tongues of dealers, suppliers, factories, collectors, and makers. Read more about this and other knife truths at my Factory Knives vs. Custom Handmade Knives page. It does not mean that these popular steels are not worth investing in, they may well be. But will they replace all tool steels in knife blades? Of course not, because every steel has its advantages and disadvantages.

Far too often, makers, manufacturers, and even knife dealers make up names and designations for the blade steel. These are not trade names originating at the foundry, they are advertising ploys. Read the section below: "What about Special Steel Designations?" for more about this.

Though there are very good tool steels, there is no super steel. You can read more details about this on my FAQ page at the question: Is there an ultimate blade? My military, police, and professional collectors know that with most production knives, the hype is thicker than fertilizer at a feed lot. Yes, there are some very good knives out there, made of fine steels. I even use many of the steels I've identified above because they are good steels. But more attention should be paid to design, fit, finish, balance, accessories, and service, because these factors are what is woefully lacking in most knife purchases and ultimately, it is these factors that determine the value of a knife. This point is so important, I've decided to give it it's own page.

Do I use these many kinds of steel? Sure, I do, but the reasonability and economy is sometimes prohibitive. Steels may prohibitively expensive to purchase, tool, grind, and make a knife with. And do you benefit from their attributes? Usually, you'll never realize that benefit, because these specialty steels were not developed for hand knives. They were developed to machine, cut, die press, and form other metals and materials for industry, usually at high feed rates, high speeds, with extreme pressures and heat, sometimes under corrosive chemical exposures. The CPM high vanadium tool steels were created and are mainly used in plastic injection molding machines. Don't think that the steel manufacturers rely on knife makers and knife buyers to produce their income. Knife blade steels are roughly 1-1.5% of the tool and high alloy steel business. Knifemakers just pick up on these steels because makers like to experiment. So they find that they all perform pretty well. I even tried some M2 once to make a knife, the performance was outstanding, but the steel had ugly waves and texture in the surface. I don't know if the user ever sharpened it, because he couldn't. Only a diamond grinder would sharpen it. So there's the limitation of usability and service too. The truth is, if more factories and knifemakers improved those six points: design, fit, finish, balance, accessories, and service, they wouldn't need to hype some specialty steel as a gimmick. Read more about that.

What about testing knife blades to determine performance and which steel is best? Read the entire page on Knife Testing at this link.

Back to TopicsHere's an email asking for clarifications about my steel discussion on my site:

Jay,

I have really been thinking hard about the knife I would like you to make me. I think I am almost done with the design of it. I have a few question about steels and their finishes. I read what you said about S30V steel and I think it is weird that the steel does have "even distribution of alloy elements" but yet it still chips at the edge. I went to the website of the people that make the S30V and S60V steels and of course they did make it sound like the "best knife steel ever" but I think I trust your opinion more. Why do you think the steel would still chip even though it has better distribution of the alloy elements? I have read a lot about the S30V steel on the internet and some people say that all steel chips at the edge, is this true?

Also, I really want my knife to have the best finish possible. Your chart on your website says that 440C has a "excellent" finish and ATS-34 has a "very good" finish. But, then in the section above the chart were you talk more about each steel it says that ATS-34 has a bit smoother finish than 440C. Does this mean that ATS-34 would have the best finish or 440C? Well, sorry for the long e-mail. I just really need to know so that I can pick the best steel for me. I'll be e-mailing you my design for my knife soon to see what you think, then we can go from there. Just let me know that you think. Thanks!!!

--B.

My answer:

Hi, B. Thanks for the thoughtful questions.

When guys talk about steel chipping on the microscopic edge, they may be talking about edge wear. Because some of the crystalline structures in steel are very hard, like iron carbides, tungsten carbides, chromium carbides, and vanadium carbides, these extremely hard particles are brittle, so they may chip off on a microscopic level. This would show up as normal edge dulling, in concert with softer components of the edge which will wear down and abrade away. The concern I wrote about on the site is that some of the manufactured knives made with CPMS30V and CPMS60V have been returned and analyzed, and reported to have a large amount of edge chipping, more than other typical knife steels. This is why I wrote about the concern, several sources relate that the long term use of these steels for knife blades is not yet proven or widely accepted by some clients. (Note: I've since talked to the manufacturer of CPMS30V steel, and discovered that in the online references to this steel type chipping at the cutting edges, both occurrences were due to austenitizing of the steel. One blade in question was overheated during sharpening, thus making it hard and brittle, and one blade was incorrectly heat treated overall. My thanks for clarification to Crucible Materials Corporation)

Does that mean that I think they are not good steels? No, they are great steels, as are so many others. If there were a super steel, you’d see it sweep the world, replacing every tool steel known or used by industry and the military. Why do you think that is not so? Each steel has different properties, and each different uses. Got a special steel you prefer? I’ll try to make a knife with it!

Please remember that people who sell particular steel types constantly hype their properties, as if that was the all-important measure of a fine knife. Mystery steels, specialty steels, and proprietary steels are not too far removed in discussion from “magical” steels… These same sites and sales people tend to ignore blade geometry, fit, finish, accessories, service, and above all, overall knife balance. The truth is, there are a whole host of steels that make outstanding knife blades. Don’t get swept up in the minutiae of alloy elements and properties, when all you want is a good, serviceable, reasonably hard, tough, and wear-resistant knife blade. None of these steels will allow you to cut a piece of agate, saw through a bank safe, or pry an engine block from a frame. The reason I throw in those ridiculous images is because that is typical of the misplaced hype many of these sites and suppliers spew. My gosh, you’ve got guys calling themselves scientists on the internet endlessly discussing the microscopic details of every compound at the cutting edge, and most people who use knives carry a box cutter to open boxes, and prep their food with cheap big-chain store kitchen knives. Why do they do this? To some it may be a valid interest, but if they were really top-flight researchers, wouldn't they be working as metallurgists in the aerospace industry, for the military, or for big universities like Midwestern? Want to know what I’m talking about? Google Ferrium C69, by Questek Steel, and Greg Olson. Amazing stuff, but it probably won’t find its way to the custom knife world in a regular way, because it’s just too expensive. Who would pay to carbon case a knife blade in a stream of hot plasma anyway?

It is, after all, only a knife. What do you expect it to do? How large, or small, how heavy or light? Can hold a decent edge, can you re-sharpen it reasonably easy? Will it be comfortable? Will it have any lasting value? Does it have a good sheath? Is it worth investing your money in?

When my grandchildren spend time in the shop with me, I make sure that they know just what fine handmade and custom knife making is about. I drill this question and into their heads until they know the answer by heart.

Question: "What is the difference between a fine handmade and custom knife, and a poorly made or manufactured knife?"

Answer: "The handmade and custom knife increases in value year after year, the other knives decrease in value."

That’s it!

Thanks for the head’s up on the steel finishes, I’ll clarify those better on the site. The suppliers are different, and some ATS34 finishes smoother, and some is more granular. The 440C has higher corrosion resistance and therefore retains its finish longer.

--Thanks, Jay

Okay, you want details. Metallurgical specifics, because you have a keen need to know just what it is that you're using, paying for, or requesting in the blade steel. Please be sure and read about the pop steels above, and all of the pertinent information on the FAQ page. Then be sure and read the several topics just below this one, for some more information. Please remember that these steels are the steels I use, and feel free to ask other knife makers about the steels they use and are familiar with.

Some wisdom:

Look, there are many good knife steels out there. When sites and discussions go on and on about steel types and properties, ad nauseam, they are often ignoring balance, fit, finish, geometry, accessories, service, and design. Don't get distracted by steel property details! The steel is just the start of the knife, not the whole. If it were, every knife made of the same steel would be the same, and every maker in the world would be out of business, not buried in orders and very expensive projects. When you see this type of site, ask to see their knives. That will tell you a lot!

What about testing knife blades to determine performance and which steel is best? Read the entire page on Knife Testing at this link.

There are a great number of tool steels, and like most custom knife makers, I have my favorites. The reason a knife maker chooses a knife steel depends on a list of requirements. Often, a client hasn't even considered some of them when he starts the conversation. The word best comes up frequently. He wants the best performance, the best durability, the best looking. "Just give me the best steel, Jay," he'll say, and then he'll have the best knife. It's just not that simple. The knife maker must balance many things in his choices, some factors not even considered by the client. Here they are in detail:

So, to select a steel type for a blade: here are the considerations: the physical factors of hardness, toughness, and wear resistance, the serviceability factors of sharpening, geometry, point service, finish, and corrosion resistance, and the financial factors of cost, value, size, and name. Seems so simple...

Hey, where is the strength requirement? Read the next topic.

Back to TopicsJay,

This is Jared Lay; my family has bought several knives from you. I bought my brother, Jeremiah Lay, a PJLT

Shank knife for him when he graduated the fire academy. Well, long story short, my brother uses the knife

all the time and just had it with him in the Philippines, after the destruction. He went into some areas

for rescue that were the first rescue people in. Just wanted you to know we love the knives you have

made and that they are doing great work across the world.

--Jared Lay

Every now and then, I read a post or article that talks about strength as a factor in knife blades. By definition, the strength of materials deals with the external forces applied to elastic bodies. When these forces are applied, deformations and stresses occur, and in extreme cases, failure in the form of bending or fracture. There are a large number of factors to consider in applied forces and metal choices, geometry, time elements, temperature, corrosive exposures, and others, which all have an effect on failure rates. You'll see the word "strong" thrown out there as if it is the all-encompassing final descriptive word to describe metals and performance.

If resistance to failure was the sole measure of a knife blade, why not just leave the blade unhardened, untempered, because that makes it the most resistant to breakage? If you have an unhardened, untempered piece of steel, you can bend it this way and that way, and stretch it, and twist it, and deform it, and guess what? It won't break. It will just deform. Eventually, it will work-harden in the area that it is most deformed, then it will become hard, and more brittle, and then it will fracture. Bend a piece of thin metal back and forth until it breaks. We've all done this; so it's easy to understand.

Strength when referring to knife blades is a generalized term. There are all sorts of strength measurements: tensile strength, stress per force of unit area, compressive strength, shearing stress, unit strain, proportional limit, elastic limit, yield point, yield strength, ultimate strength, and more! Read about these strength factors in the section below: More about Toughness and Ductility for greater details about strength.

Many materials are relatively strong. When people and websites and sales vehicles claim that their blades are strong, or very strong, or have the greatest strength, please have a strong stomach for hype (sorry, bad pun). There is so much more to strength that a generalization like this has no place on the most detailed information source in the world, the internet.

Yeah, it's strong. yeah, it's tough, yeah, it's hard and shiny. Kind of an ambiguous, weak claim, isn't it? More about Toughness and Ductility

Back to Topics

Another balance question. There are materials that absolutely will not corrode. Ceramic comes to mind. Titanium is nice. But these are not typical blade steels, and there is good reason. They are several orders of magnitude softer than any good knife blade. These materials are either brittle and unsharpenable (ceramic) or have no wear resistance or low tensile strength (titanium). Though you may see these materials and others (monel, bronze, beryllium copper, aluminum-bronze, and copper alloys) used in making non-sparking, non magnetic tools for special hazardous materials exposures and explosive environment applications, they are not hard, wear-resistant, tough, and durable tools.

What about other, lower carbon stainless tool steels? In my opinion 440A and 440B stainless steels do not make superior knife blades even though they may be a bit more corrosion-resistant than 440C. These steels do have at least 0.60% carbon and are capable of being hardened and tempered, but are not nearly as wear-resistant as 440C. There is a reason that nearly all highly corrosion-resistant ball bearings, shears and tools, and high pressure valve seats are made of 440C.

One may claim that CPMS30V, CPMS60V, and CPMS90V are slightly more corrosion-resistant than 440C, but since they can not be mirror finished, their rough surface may actually accelerate corrosion (see my book clip on finishes below). There are a host of other metals used in knife blades and a large variety of performance options, so nothing is set in stone here. That is why any maker worth his salt will use a variety of steels, and yet still have his favorites.

Back to TopicsThe phrase edge retention is a recent one and pops up in conversations and discussions about knives. It's a fancy way to describe wear resistance, pure and simple. In the metalworking and machinery trade, wear resistance is the resistance to wearing away of the surface of a metal on an exposed edge, surface, or area. It's important to know that wear resistance is mostly subjective, that is, it is not specifically calculated with technical apparatus, but observed by experiment and comparison. These wear resistance factors can only be determined by generalities, such as best, fair, medium, and poor when compared to other metals; there is no specific measurement to assign a numerical value to wear resistance (or edge retention).

Why isn't there a specific number, designation, or assignment pertaining to individual metal alloys and wear resistance? It is because there are far too many factors in play in the knife to make any specific comparison. The steel type is not enough information; as the alloy may vary in content from manufacturer to manufacturer, and even between foundry runs. The heat treating may vary between tested blades, the actual temper of the blade may have slight variations along its length. The geometry is extremely variable, and even if the blades appear the same, variations in grind thickness, sharpening angles, and edge faces mean that there can be no specific and detailed measurement. The surface finish varies even along the cutting edge length. Even in machine tools like drills, milling cutters, and other tools used in the metal machining trades to cut, there are no specific wear resistance values, only generalities. In order to be specific in hand knives, one would have to make a knife blade out of every material available, created to the exact same dimensions (within a millionth of an inch), finish all surfaces exactly the same (which is impossible), before the specific comparison could be made. Our test knives would have to have the exact same geometry of profile curve, sharpening angles, and angle of approach to the cutting task. One would have to negate the other critical factors in knife blade construction, like toughness (often more important than wear resistance), corrosion resistance, and sharpenability itself!

What about testing knife blades to determine performance and which steel is best? Read the entire page on Knife Testing at this link.

In advertising, you may see stacks of paper clamped in blocks with knives mounted to an apparatus that forces the blade into the paper repeatedly until it quits cutting, signifying dullness. You may see knives shaving wood, paper, cloth, or cutting rope over and again until the edges dull and this is supposed to prove one steel, blade, or process of knife making is superior to another. Frankly, all of these so-called tests are subjective. Subjective means "existing in the mind" and this is what people who perform these tests want to happen in your mind. They want you to think that (shockingly) their product is superior while they hope you'll ignore bad fit, weak design, cheap materials, amateur skill, poor finish, weak construction, lack of accessories, and the other factors that make a knife an investment or critical application knife vs. a simple, throwaway tool.

What does this have to do with edge retention (actually wear resistance) of the modern handmade knife? It's simple. Everybody wants a knife that has high wear resistance, that is, one that holds an edge a long time between sharpenings. With modern, high alloy tool steels, high wear resistance is (or should be) a given when compared to plain carbon or low alloy tool steels (more about these at this bookmark). In the chart below, you can see a comparison of wear resistance between the steel alloys I use. Please remember to balance these with toughness, grind geometry, and corrosion resistance as the edge also corrodes away as well as wears away. If the blade edge is too hard, it's brittle, and can actually chip away microscopically, presenting as wear, particularly if the blade is ground too thin. The maker must balance the wear resistance with the grind geometry, the profile shape, the intended use of the knife, and the service factor of sharpenability, because sooner or later, every edge dulls and will have to be sharpened.

For most of these factors, it's fairly simple; the knife maker should be able to balance the knife type, the intended use, the blade geometry, the steel type, the grind geometry, the edge thickness, the weight of the blade, the corrosion resistance needed, and the service factor with a client's ability to pay for the blade. Yes, the financial factor is also one rarely mentioned.

If you're still asking for the best edge retention, I'll clearly point you to the material that has the highest hardness known. That would be diamond. Oh, there are other carbon nano-particles that claim to be harder, but they are a bit more expensive to produce. I'm sure that millions of dollars will give you the performance you may need, in having a knife that never, ever needs sharpening. If you can't afford this, I would suggest a reasonable balance between all those other factors listed on this page.

What about testing knife blades to determine performance and which steel is best? Read the entire page on Knife Testing at this link.

Please help to stop wives' tales, knife myths, and misconceptions in our trade through education.

Back to TopicsI had a good laugh when I saw on another site that I've been accused of pushing a particular type of tool steel by self-proclaimed experts on knife blade steel (By the way, when you see these sites, ask how many knife blades the expert has actually made. Then ask to see a list of military and professional clients he's made knives for. Then ask to read the testimonials of support submitted by his military and professional clients. See mine here in over a dozen pages with hundreds of photos, descriptions and testimonials).

I don't push any particular steel. If you have a special steel you prefer, please, by all means, let me know why, and I'll make a knife out of it for you! I don't have an agenda about the steels I use, I just have my favorites. There are new ones all the time, and you might be surprised to find out that I've tried quite a few. I don't get kickbacks, or promotional payment, or some kind of benefit from suggesting a particular type of steel. I also am very clear about the steels I do use, and if you have a particular and specific question about the type of steel used in a knife I make for you, by all means, ask! Please don't ask about steels other makers use, feel free to ask them. Want to know what is being overlooked by experts arguing about steel types? Fit, finish, balance, design, accessories, and service.