Jay Fisher - Fine Custom Knives

New to the website? Start Here

"Bellatrix"

This page is about knife maker's marks, stamps, logos, signatures and emblems in general, and my maker's mark in particular. There isn't a great deal of information about knife maker's marks on the internet, and I hope that this will answer some of the many questions people have about the mark. This is not a catalog of maker's marks, and I have no interest in creating one, but I do know that some interests are moving in that direction, which is a good thing. I look forward to a day when maker's marks are registered in some international database, but today, I know of no such thing. What a great project this would be for a knife aficionado, as he would be able to look at just about every kind of knife made!

The most important thing to remember on this page is:

A knife maker's mark is the individual logo, emblem, signature, design, or text that he puts on the blade to signify its origin. In factory knives it is often a tang stamp to identify the manufacturer. Traditionally, it is placed only on the blade, usually near or on the ricasso, on the obverse side of the blade, but there are some variations of placement. See the Knife Anatomy page for specific details about knife location and parts.

A mark signifies the origin of the knife, and thus its source, origin, and ultimately value in the knife world. Like a brand name, a maker's mark identifies and individualizes a knife. A knife may have many owners in its lifetime, but only one original maker, and (hopefully) one original maker's mark. An unmarked knife is essentially worthless, as it is an assemblage of miscellaneous parts, of unknown origin by an unknown craftsman. The knife has no history, no key to the materials it is made of, no idea of the span of time that it was made. Imagine a handmade firearm or work of art that does not have a signature or identifying stamp and you can easily see why a knife without a maker's mark is only a piece of steel. Even a decent screwdriver has a brand name!

If a maker doesn't have a long established reputation in knife making, and doesn't have some type of reference, source, or authentication of his maker's mark, his knives will be lost to history, and the knife deemed essentially valueless. I've seen many knives over the years that have simple initials as a makers mark, and, sadly, that is a hopeless and valueless identification method. One might argue that the original owner knows who's initials they are, but once that information stops being passed along, the knife becomes valueless. Unless the knife is accompanied by extensive information (and on these types of knives, there is usually none), no one knows who made it, what it's made of, where the knife came from, generally when it was made, and how much work on the knife was done by the maker, or how much was done by other craftsmen. They can't find out if it's a kit knife, or even from what country the knife originated.

As a serious knife maker produces knives, his name, his logo, his identification gathers interest and notoriety, and all of his maker's marks from the beginning of his knife making career or knife making endeavors can become more valuable.

Factories often standardize the text component of their mark, and individual knife makers tend to do the same. Makers may design a custom mark or use simple text; their mark may contain graphics and text, dates, locations, and other information that the maker deems important. Some are stylized, some are simple. Every successful modern knifemaker usually creates an original mark to identify his work.

The knife maker's mark is usually placed on the obverse side of the blade. The obverse is the usually observed side of the knife, and I detail this location on my Knife Anatomy page. Some makers deviate from the fairly standardized practices in placing their mark in unusual places on the knife or blade. Some apply it to the tang flat, some engrave it on the fittings, and some mark it on the reverse side instead of the obverse. There is no rule here, just common practices.

For myself, I usually place my mark in the grind (not on the flat) for several reasons. One, the depth and area of the grind offers enough space to place the mark. I've known of makers who purposefully leave grinds small so they have a place on the spine for their mark. Two, I'm very proud of my grinds, and want the mark to sit in this predominate location. Third, it's challenging to place most maker's marks in the concave cut of the hollow grind, as most marking methods are designed for flat surfaces. I like to be a bit different.

There are many differences in knife makers' marks, and I encourage you to look around the internet and see how each individual maker puts his mark on his knives; it is an interesting subject.

I believe that In addition to the maker's mark, the knife maker should include essential information with the knife purchase, in as durable a form as possible. This information should include the name or number of the pattern, the steel type, the hardness or temper, the fitting materials, handle material, and the accoutrement materials. The information should include who embellished the knife if the original embellishment was not accomplished by the maker.

The information provided with the knife is the record of origin. This information is essential in establishing an investment value for the knife. Some knife organizations suggest a "Certificate of Origin" to be given with each knife to provide some of these details. Other makers include the information on the back of a laminated business card, others simply include the information on paper form.

Unfortunately, a piece of paper can be easily defaced or discarded, and it is up to the knife owner to maintain his own records if he desires to realize any investment appreciation for his knives. For some clients, this is simply not in their interest.

For my own knives, I include an engraved co-extruded acrylic nameplate with the information cut into the plastic accompanying each knife, which should last indefinitely. It has all my contact information, the pattern design, steel type, hardness, fitting material, handle material(s), sheath, stand, or case materials and other relative information.

A new source of custom and handmade knife information is available and will become more predominant in the future, and you're looking at it. The knife maker's own website can be a source of valuable data on the knife if the maker chooses to include that data. Currently, there are no restrictions that prevent large, inexpensive data banks of past knives (including photographs and specifications) being maintained and available to the public through the internet. I offer just such a service on my Featured Knives pages with links to individual and noteworthy knives.

Additionally, I offer CD ROM catalogs of my previous works. I continue to update them in very high resolution photographs. The digital information age has given us several substantial and reasonable ways to maintain a library of our works.

There are several common practices that are currently used in putting a maker's mark on to the knife. Most of the marks are placed on the steel blade, as this is usually the most durable location on the knife. Older methods are still being used, and some interesting modern methods are available to the individual maker.

A maker's mark may or may not have a location (city, state, or country) as part of the mark. I know that some makers consider this important as an indicator of generally when the knife was made, as they have moved around during their career.

A maker's mark may be generalized to a company, and I think this is a bad idea. It hints that the knife is not made by an individual but by a group, manufacturer, or some faceless entity.

Sometimes questionable graphics are included in the makers mark. The maker should be certain that he and his clients are comfortable with the images presented, as they can say a lot without actual text.

Decades ago, an old and successful knife maker told me, "In this business, name is everything." While this is exaggerated somewhat, personally and professionally, I believe that the name itself is the most important thing that any maker can put on his knife. Though the knives you create, your clients, your level of craftsmanship, and your longevity are just as important, he meant that all of these attributes are identified with your name.

I believe in using either a full name, or as close to it as possible. Knives marked Fisher are actually fairly common in the knife world, and I get asked about them frequently. The last name alone is not enough of an identifier, and your work can be easily confused with the work of another. Even the moniker J. Fisher can encompass a significant list of other makers, so I believe it's best to use as much of the name as possible or to stylize it so it is distinctive. This is important not only to the maker, but also to his clients as the long term value of the knife is directly linked to the maker's mark.

If work was done on the knife by an embellisher (engraver, scrimshander, or carver) their name is seldom included with the knife maker's mark, but is often on accompanying information that goes with the knife. This practice is common in this industry, and there are a wide range of opinions about it. Should credit be given to the person who engraves the knife in a permanent fashion marked on the knife? What about someone who scrimshaws the handle? What about a carver who shaped the handle? This can be a heated topic, but thankfully, one I don't have to address. I accept no other artists on my work; my engraving, etching, carving, and embellishment is all my own. If you see it on my site, and it has only my name on the blade, all the work done on the knife is done by me.

If other knife makers have worked on the knife, I believe it's important to include their names as well. I have several collaborations on the site, and I will always include their distinctive names on the maker's mark as well as my own.

Collaborate means literally: to labor together. Collaborative knives are works that are made together with another knife maker. These are different than the works listed in the previous topic above, where specific portions like engraving or etching are farmed out to other artists; these are two knife makers working together on one knife. When a collaborative is made, both makers have their marks put on the knife. When you see a knife with two maker's names or marks on the blade, this is a collaboration.

If a knife is made by several makers and only one maker's name appears on the completed work, this is a misrepresentation of the authorship of the piece. I've seen this done before, where a singular knife maker has others working in his shop, making the knives, and then has only his name on the blade. This is typical of the small boutique shop that uses a maker's name on their knives. There are some substantial knife factories that use the original maker's name, though the guy whose name appears on the blade is long dead. The knives may be made by the descendants of the original maker or a complete stranger; it does not matter. When knives become manufactured; when more than one person works in a shop that claims an original name, the value of the knife drops considerably. The name becomes a logo, then a trademark, as the knife making becomes less and less specific and is completed partially or entirely by workers whose names do not appear on the product.

In my own collaboratives, if another maker works in any way on the knife, his name also appears at the maker's mark. If I work on someone else's knife in any way, my name appears also at the maker's mark. When you see or own a knife with only my maker's mark on the blade, you have my assurance and guarantee that I have done all the work on the knife, every single bit, including sweeping up its metal swarf from the shop floor.

When a knife is made in collaboration and both maker's marks appear on the blade, it does not devalue the piece, and in some cases, can actually increase the value of the knife. It depends on whose names are on the blade and what this signifies in the progression of both of the artist's and craftsman's work. For instance, when I've made collaborative knives with James Beauchamp and Rusty Russom, both of our maker's marks signify that these are works by an established maker (me) and new makers. Eventually, these new makers may create knives with only their own maker's mark. These transitional knives serve as a record of the new maker's journey and career in this field. Depending on the direction and scope of those new makers (and this old one!), the knives may serve as valuable, unique milestones in the progression. Owning one of them means owning an early work of the new maker, while exhibiting the quality an cooperation of the established maker. This translates to long-term value, and establishes a place in the history and tradition of the works.

In my own work, I actually only rarely collaborate. Along with the two new makers listed, I've done a few collaborative works with Gerry Hurst, just before he died. And in those works, yes, both of our names appear on the blade. The most important thing is honestly representing what and who has created the piece.

Artistic growth, reputation, and momentum has caused my own maker's mark to evolve. My first maker's mark was an artistic design similar to a butterfly, made of my first name and last name initial. I took the letters Ja and combined them with f in lowercase to make a Jaf that resembles a butterfly or wings. I thought that my mark ought to be unique, and the y in my first name was silent anyway, so it worked out well.

After a while, I decided to progress to photo resistive etching, and my mark incorporated the same butterfly motif. I added the rest of my last name, and to demonstrate clearly the extreme resolution and fine detail possible with my new marking method, I added the words Quality Custom Knives in a triangular fashion around the signature, which was also the name on my first storefront studio in Magdalena, New Mexico. I added two identical matching flourishes to fill out the design into a more rectangular shape, and to add an artistic component. The entire mark was less than 0.3" x 0.5" in size, and I've even used a smaller mark that is one third that size! It may take a magnifying glass to read the mark, but you can make out every line.

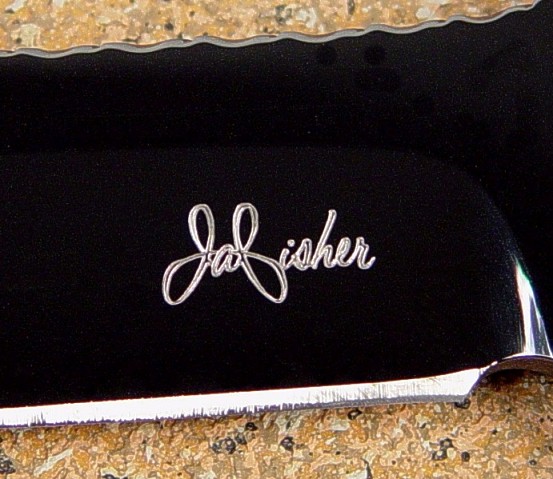

My third design, which I started using exclusively in 2007, is simply my butterfly signature, hand-drawn and reduced. After nearly 30 years and 18 of them full-time as a professional knife maker, literally thousands of knives, and rational direction from my wife, it seemed that the words Quality Custom Knives were redundant. The new mark is clean, clear and simple, and my knives can not be mistaken for knives made by others. Who knows, in another fifteen years of so, I may change my mark again. The added benefit of this is that my particular mark will identify roughly when the knife was made, for future generations, long after I (and maybe you!) are gone.

This is my first maker's mark, and exists on knives I made from 1979 to 1989. It was a bit rough, made from hand-cut materials for a mask, and done with the electric etching technique, it is clearly original, and easily identifiable. Not a lot of information, though, about who JaF was! If you have a knife with this logo only on it, you have a very early Jay Fisher knife indeed!

This is my second maker's mark, used from 1988 to the end of 2006. The fine lines etched in the blades are certain indicators of the high detail. The neat thing is you can take a magnifying glass and see the tiny partial cross on the t of the word Custom on the steel. This component is about 1/10,000 of an inch wide!

This is my third evolution of my maker's mark, a hand-inked design that is simply my artistic signature and long standing reputation. It's clear, concise, and neat, and anyone looking up the name: Jafisher on the internet will end up here! The feedback for my new mark has been great.

| Main | Purchase | Tactical | Specific Types | Technical | More |

| Home Page | Where's My Knife, Jay? | Current Tactical Knives for Sale | The Awe of the Blade | Knife Patterns | My Photography |

| Website Overview | Current Knives for Sale | Tactical, Combat Knife Portal | Museum Pieces | Knife Pattern Alphabetic List | Photographic Services |

| My Mission | Current Tactical Knives for Sale | All Tactical, Combat Knives | Investment, Collector's Knives | Copyright and Knives | Photographic Images |

| The Finest Knives and You | Current Chef's Knives for Sale | Counterterrorism Knives | Daggers | Knife Anatomy | |

| Featured Knives: Page One | Pre-Order Knives in Progress | Professional, Military Commemoratives | Swords | Custom Knives | |

| Featured Knives: Page Two | USAF Pararescue Knives | Folding Knives | Modern Knifemaking Technology | My Writing | |

| Featured Knives: Page Three | My Knife Prices | USAF Pararescue "PJ- Light" | Chef's Knives | Factory vs. Handmade Knives | First Novel |

| Featured Knives: Older/Early | How To Order | 27th Air Force Special Operations | Food Safety, Kitchen, Chef's Knives | Six Distinctions of Fine Knives | Second Novel |

| Email Jay Fisher | Purchase Finished Knives | Khukris: Combat, Survival, Art | Hunting Knives | Knife Styles | Knife Book |

| Contact, Locate Jay Fisher | Order Custom Knives | Serrations | Working Knives | Jay's Internet Stats | |

| FAQs | Knife Sales Policy | Grip Styles, Hand Sizing | Khukris | The 3000th Term | Videos |

| Current, Recent Works, Events | Bank Transfers | Concealed Carry and Knives | Skeletonized Knives | Best Knife Information and Learning About Knives | |

| Client's News and Info | Custom Knife Design Fee | Military Knife Care | Serrations | Cities of the Knife | Links |

| Who Is Jay Fisher? | Delivery Times | The Best Combat Locking Sheath | Knife Sheaths | Knife Maker's Marks | |

| Testimonials, Letters and Emails | My Shipping Method | Knife Stands and Cases | How to Care for Custom Knives | Site Table of Contents | |

| Top 22 Reasons to Buy | Business of Knifemaking | Tactical Knife Sheath Accessories | Handles, Bolsters, Guards | Knife Making Instruction | |

| My Knifemaking History | Professional Knife Consultant | Loops, Plates, Straps | Knife Handles: Gemstone | Larger Monitors and Knife Photos | |

| What I Do And Don't Do | Belt Loop Extenders-UBLX, EXBLX | Gemstone Alphabetic List | New Materials | ||

| CD ROM Archive | Independent Lamp Accessory-LIMA | Knife Handles: Woods | Knife Shop/Studio, Page 1 | ||

| Publications, Publicity | Universal Main Lamp Holder-HULA | Knife Handles: Horn, Bone, Ivory | Knife Shop/Studio, Page 2 | ||

| My Curriculum Vitae | Sternum Harness | Knife Handles: Manmade Materials | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 1 | Blades and Steels | Sharpeners, Lanyards | Knife Embellishment | ||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 2 | Blades | Bags, Cases, Duffles, Gear | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 3 | Knife Blade Testing | Modular Sheath Systems | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 4 | 440C: A Love/Hate Affair | PSD Principle Security Detail Sheaths | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 5 | ATS-34: Chrome/Moly Tough | ||||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 6 | D2: Wear Resistance King | ||||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 7 | O1: Oil Hardened Blued Beauty | ||||

| The Curious Case of the "Sandia" |

Elasticity, Stiffness, Stress, and Strain in Knife Blades |

||||

| The Sword, the Veil, the Legend |

Heat Treating and Cryogenic Processing of Knife Blade Steels |